Post-Vacation Blues: Why Coming Home Feels So Hard

The science of re-entry dread, time compression, and why your self-governance feels more expensive for a few days

I’ve been travelling with my family for around 3 weeks, and I can’t deny it… it has been really fun.

I’m writing this as we fly back to our home, and nostalgia already hits; loved ones are already missed, and all the experiences we have had start to pop back at high speed.

Still, another feeling comes with it.

The dread of coming back to reality.

This Is Not Only Sadness

I used to treat this as a normal goodbye. You miss people, you miss the rhythm, you go back to your life. That explanation still holds, but it’s not the whole thing.

Because getting home doesn’t only affect what you feel…it affects how you move.

Nothing breaks loudly. Your life doesn’t collapse. You don’t suddenly become a different person. Things just get harder to do cleanly, and the cost shows up in places most people don’t connect to a vacation. You feel it in your patience first. In your tolerance for friction. In how quickly you can switch from being present to producing again.

The confusing part is that you can genuinely like your life and still feel that resistance in your body. You can like your job, like your home, and like your routine and still feel off for a while.

That’s the problem I want to talk about in this reflection, because it’s easy to misread it as “something is wrong with me.”

Life Kept Moving Without You In It

You get home carrying a whole internal state, and, without saying it, you want a softer landing. You want the day to be gentler. You want people to read your face.

Then you step back in and realize the world kept moving without you.

Your inbox grew. Your calendar stayed packed. Decisions kept lining up. Even the people you love are living their own day, and they are not inside your nervous system, so they can’t feel the contrast you feel.

No one is doing anything wrong. Still, that gap takes a toll. The transition becomes private. You’re merging two rhythms alone, while the day treats your landing like a normal Tuesday.

That’s when it hits you: the trip didn’t just end, it ended fast.

When Fun Compresses Time

That sensation — of your trip not lasting long — happens because when we’re having real fun, days shrink.

You blink and it’s late again. You think you still have plenty of time, and suddenly you’re packing. Then the trip ends, and part of you feels like you never had enough hours to enjoy what you came for, even though you were there for all of it.

You just want the time to stop and be able to hold the moment. To cherish it; to soak yourself in it.

The thing is that there’s a difference between how time feels while you’re living it and how it looks when you remember it later. Those two do not behave the same way, which could help explain why something can feel fast in the moment and still feel full in hindsight1. Flow research points to a related feature too: deep absorption often comes with time distortion, frequently experienced as time passing faster than usual2.

As a consequence, the ending lands abruptly. Not because the vacation was objectively short, but because your experience of time was compressed.

And when time feels compressed, reward gets concentrated.

Your System Got Used To A Different Reward Rhythm

Vacation isn’t just rest. It’s a different reward environment.

Novelty is baked in. Connection is baked in. Meaning shows up without you manufacturing it. Even the hard parts can feel worth it because they belong to a story you chose.

That’s why visiting new places and living new experiences doesn’t stop being exciting.

The problem is that you get used to that rhythm faster than you expect.

At a basic level, your brain is learning what to pursue. One of the clearest ideas in the neuroscience here is that dopamine neurons track reward prediction error, the gap between what you expected and what you got, and that signal behaves like a teaching signal for learning3.

A good trip delivers a steady stream of small, better-than-expected moments. Then you’re back at home, and the reward density drops fast. Home becomes predictable again. Work becomes delayed payoff again. Responsibility comes back in bulk.

That drop can surely feel like a crash. People call it withdrawal because the contrast is abrupt, even though it’s not the same thing.

Once the crash shows up, the next question is always the same: does it fade, or does it stick?

The Fade-Out Has A Shape

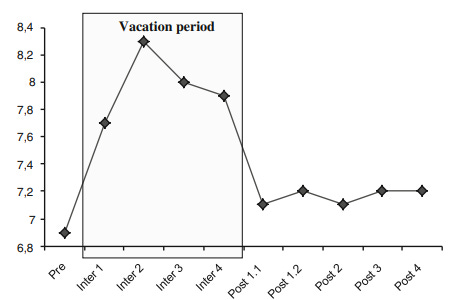

There’s research that matches the curve people report. A meta-analysis found vacations have positive effects on health and well-being, and that these effects soon fade after work resumption4. A field study following employees through longer vacations found health and well-being increased quickly during vacation, peaked around the eighth vacation day (see Figure 1), then returned to baseline within the first week after work resumed5.

So if the glow fades fast, you’re not inventing it.

For many people it softens within days, sometimes within a week. When it lingers longer, it often arrives in waves rather than as a constant67.

That’s the pattern at the group level. Here’s what it looked like for me.

Where It Used To Hit Me Hardest

For a long time, this stage would hit me hard.

I would get sluggish, irritable, and sometimes even resentful. Not because people did anything wrong, but because I wanted them to understand what I felt without me having to explain it. They didn’t have to. They couldn’t. That mismatch created friction, and the friction would spread.

The feeling itself was instinctual. What made it expensive was the story that followed it.

Lately, awareness has helped soften the blow. The feelings still show up. I still miss people. I still feel the drop. The difference is that the ripples don’t travel as far once I notice them, and the voice in my head is easier to tame when it starts trying to turn the experience into a verdict.

For me, the first cues look like a shorter fuse, a heavier start, more procrastination than usual, and the urge to rush through normal things. The day hasn’t changed. My state has.

Before You Call It A Failure

Now, here’s why this gets misread so often.

A state shift changes your judgment while it’s happening. Psychology has a name for this family of mistakes: hot-cold empathy gaps. When you’re calm, you mispredict what you’ll do when you’re tired or emotionally loaded. When you’re in the loaded state, the feeling starts to look permanent8.

Stress makes that misread sharper because it hits the systems you rely on for self-governance, meaning the ability to realign to your values, principles, and beliefs on purpose. Even mild acute stress can rapidly impair prefrontal cortex functions tied to working memory, planning, and cognitive control9. Under stress, behavior also tends to shift toward habitual control and away from goal-directed control, which is another way of saying your defaults get louder even if your values didn’t change10.

Getting home can carry all of that in one package: sharp contrast, demand spike, private transition, tired body, and a brain that still hasn’t caught up.

So when the voice shows up and tries to turn this into proof of weakness, treat it as a state, not truth.

If the dread never fades, or if it keeps showing up as something darker than a transition cost, it might be pointing at something deeper than travel. Most of the time, though, it’s simply the cost of switching rhythms.

What You Can Take Home

If you take anything from this reflection, let it be this.

Getting home can feel heavy even when your life is good. Time can feel compressed when you’re deeply engaged, which is part of why vacations end with that it-went-too-fast sting. Then you’re back, and the world is already moving at full speed, which makes the contrast sharper and more private.

When that happens, self-governance costs more for a bit. You feel it in your patience, in your energy, and in how much friction you can tolerate before your defaults start looking attractive.

Tomorrow’s paid companion turns this post-trip stretch into something you can handle on purpose, so you can shorten the drift window and keep the ripples from spreading when dread shows up.

For now, my invitation is simple. If you’re going through this right now, give yourself some grace. Notice your cues. You’ll have your own version, but it will have a signature once you start paying attention. When you spot them, respond in the small ways you already know help you soften the blow. It won’t erase the feeling, but it will lower the cost of the week.

Have a wonderful week!

✨ Ideas Worth Exploring

If this piece resonated, here are a few more that go hand-in-hand.

Block, R. A., & Zakay, D. (1997). Prospective and retrospective duration judgments: A meta-analytic review. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/BF03209393

Rutrecht, H., & Wittmann, M. (2021). Time Speeds Up During Flow States. Time & Society / Time (journal). https://brill.com/view/journals/time/9/4/article-p353_353.xml

Schultz, W. (2016). Dopamine reward prediction error coding. Current Opinion in Neurobiology (PMC). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4826767/

de Bloom, J., Kompier, M., Geurts, S., de Weerth, C., Taris, T., & Sonnentag, S. (2009). Do we recover from vacation? Meta-analysis of vacation effects. Journal of Occupational Health. (PubMed) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19096200/

de Bloom, J., et al. (2013). Vacation (after-)effects on employee health and well-being… Journal of Happiness Studies. (Abstract) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10902-012-9345-3

de Bloom, J., Kompier, M., Geurts, S., de Weerth, C., Taris, T., & Sonnentag, S. (2009). Do we recover from vacation? Meta-analysis of vacation effects. Journal of Occupational Health. (PubMed) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19096200/

de Bloom, J., et al. (2013). Vacation (after-)effects on employee health and well-being… Journal of Happiness Studies. (Abstract) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10902-012-9345-3

Loewenstein, G. (2005). Hot-Cold Empathy Gaps and Medical Decision Making. (PDF) https://www.cmu.edu/dietrich/sds/docs/loewenstein/hotColdEmpathyGaps.pdf

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. (PubMed) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19455173/

Schwabe, L., & Wolf, O. T. (2011). Stress-induced modulation of instrumental behavior: From goal-directed to habitual control of action. Behavioural Brain Research. (PubMed) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21219935/

Post-vacation blues isn’t just missing the beach. It’s the psychic sting of coming back to a life

that wasn’t actually lived while you were “at home.” Vacations make absence of attention visible, not absence of joy. What hurts is not the end of rest. It’s how shallow our presence was before we left.

- Double🆔️