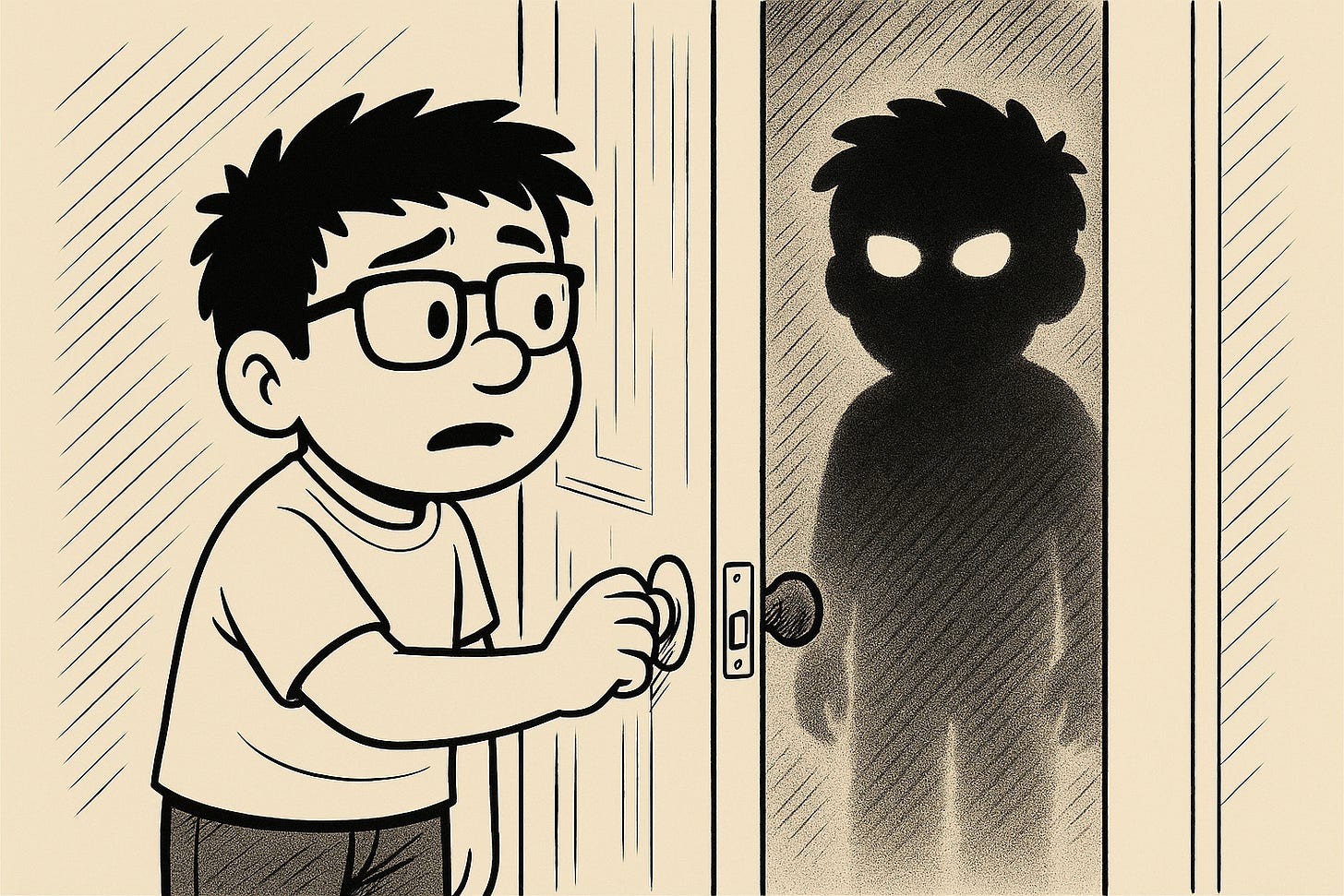

Don’t Let the Intruder Run the House

When self-doubt sounds like reason, awareness becomes your guardrail

I met the intruder on a dog walk after dinner. Streetlights on, leash in my left hand, and my wandering mind still settling the day.

He slipped in as he does when I’m running low. Same lines as always:

Why keep pushing?

What if this stalls?

Are you sure this matters?

He steered the thoughts toward my personal work, including Self Disciplined and the pieces around it.

My job matters to me; this time he aimed at the personal side. I didn’t try to outtalk him. I let the words sit. I wanted to see what they were made of.

This wasn’t a crisis or anything like that; it was just a tired brain after a long week. I’ve been mentoring interns, taking the commute instead of staying home, keeping the ball rolling on multiple projects, and answering messages I should have answered earlier.

I wrote at night.

I slept less than I said I would.

The intruder likes weeks like that. He doesn’t need a door; he finds a crack.

Awareness doesn’t erase the intruder.

Awareness sets the room.

What the Intruder Sounds Like

The intruder never argues with facts. He pokes soft spots.

He sounds like this:

You’re spreading yourself thin. Nothing will land.

You lost momentum. People noticed.

You’re writing into the void. Admit it.

You say discipline, then you drift like anyone else.

Self Disciplined isn’t moving. Admit it.

He pulls from whatever is nearby: a comment someone made about growth, a number that moved slower than I hoped, a draft that looked better in my head than on the page — anything close enough to sting.

🛑 Before We Continue

Let me take a second to share some reminders.

👉 Check out my book campaign!

I’m writing a book to spread the word on Adaptable Discipline, and I need your help. I created a campaign in Publishizer to bring visibility to publishers. And the best way to do that is through pre-orders.

⏳ The clock is ticking; we only have 1 more day!

Check it out and help me by pre-ordering the book or spreading the word.

👉 You don’t need more motivation. You need a map when your brain drifts

Lock in $7.99/month before Dec. 1st (rising to $11.99).

Weekly Katas, Sequences, and Mental Models you train on easy days and deploy when focus breaks.

He doesn’t bring new information.

He recycles.

He speaks in my voice to make it sound true.

I’ve fallen for it before. I’ve paused projects that only needed a day of rest. I’ve called a slump a verdict. I’ve opened the door and let him walk straight to the center of the house.

That is the part that hurts when I catch it.

What Feeds the Intruder

This week there were reasons I was more open to him.

I changed my routine to be in the office, and it netted two hours less with my family.

I led an intern team, which meant more decisions and the need to stay on top of everything.

There were also more small switches of attention.

At home I tried to keep pace with what I promised I would publish for Self Disciplined. I looked at subscriber numbers on the dashboard and wondered if they would move.

I opened social media and compared myself to people who post ten times a day. I know I shouldn’t, but I’m human after all.

That was enough fuel. He didn’t need more.

None of this was crazy or dramatic; it felt familiar. The intruder grows in the small pile-ups that put weight on everything.

That’s the surface. Underneath, fatigue tilts the system so his voice carries farther.

Here’s what the brain does with a week like that.

Your Brain as the Intruder’s Main Target

Take the week I shared: lack of sleep, many decisions, and comparisons close at hand.

The system tilts; everything starts to slide.

Alarm circuits speak louder, and the regulator loses grip.

Beep, beep, beep…

That tilt is the opening the intruder uses.

Your brain becomes the playground, and it starts acting out:

Alarms rise. After a single night without sleep, the amygdala reacts more to negative cues. Coordination with prefrontal control drops. Alarms up, brakes down1.

Context narrows. Fatigue reduces attention, working memory, processing speed, and reasoning. With fewer pieces of context on the mental screen, one slow metric or one sharp comment fills the frame and looks like the whole story2.

Urgency dominates. Under strain, attention and memory favor what feels immediate. Nuance fades as arousal biases the system toward the signal that shouts the most3.

Correction slows. Sleep loss weakens error-monitoring signals linked to the anterior cingulate and control networks. Friction is noticed later. Adjustment comes slower. Loops repeat longer than they need to4.

That is the chain: alarms rise, brakes weaken, context shrinks, urgency wins, and correction slows.

The intruder steps into that tilt and claims more room than he deserves.

This is a temporary state, not a fixed self. It clears as your system regains balance.

Turning the Intruder into a Guest

Changing the uninvited’s status works better. We invite the intruder in.

He becomes a guest.

This deliberate act changes how the scene plays out in the brain. Naming the intruder as a guest tones down the alarms and lets prefrontal control regain grip.

Saying what is here is affect labeling. In brains, affect labeling links to lower amygdala reactivity and greater right ventrolateral prefrontal activity. The alarm loses gain as control engages5.

Labeling alone is not enough, though.

The house needs rules, stated in plain terms, the way you would with any guest: you can sit, you can talk, but you don’t move furniture, and you don’t set the plan.

In cognitive terms, that is a reframe. Reappraisal recruits prefrontal control networks and reduces negative affect across studies and meta-analyses67.

With rules set, coexistence is possible without handing over the keys. A guest can be present without running the house.

Acceptance and mindfulness map to this stance. Attention stays open. Reactivity drops. Behavior stays aligned. Trials and meta-analyses show better regulation and measurable changes in monitoring and regulatory networks89.

Agency stays visible. Boundaries are strong, tacit rules you keep. Perceived control buffers stress responses and helps performance under load. Even reframing stress as fuel instead of a threat leads the system to adjust in that direction1011.

Turning the intruder into a guest is not softness.

It is a compact way to label, reframe, allow, and keep the room yours. He can speak from the corner, but the furniture stays untouched, and the day remains yours.

Takeaways

Letting the intruder damage us opens the door for others to do the same.

He has the biggest reach. Nobody else holds that level of influence over you.

Everyone else is an echo of the same thing. When the intruder becomes a guest and stays in his corner, nobody touches the center.

In the paid companion, I’ll share how I handle the guest once he’s in the room and what boundaries to hold without turning life into a fight.

Have you crossed paths with the intruder?

Share your experience in the comments 👇.

Have a great weekend!

✨ Ideas Worth Exploring

If this piece resonated, here are a few more that go hand-in-hand.

Enjoying this? Support the mission.

I write Self-Disciplined to help more people build real, lasting discipline — without burnout. If my work has helped you, consider supporting it with a coffee or becoming a member.

Yoo, S.-S., Gujar, N., Hu, P., Jolesz, F. A., & Walker, M. P. (2007). The human emotional brain without sleep: A prefrontal–amygdala disconnect. Current Biology, 17(20), R877–R878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.007

Lim, J., & Dinges, D. F. (2010). A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 375–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018883

Mather, M., & Sutherland, M. R. (2011). Arousal-biased competition in perception and memory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(2), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611400234

Tsai, L.-L., Young, H.-Y., Hsieh, S., & Lee, C.-S. (2005). Impairment of error monitoring following sleep deprivation. Sleep, 28(6), 707–713. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/28.6.707

Lieberman, M. D., Eisenberger, N. I., Crockett, M. J., Tom, S. M., Pfeifer, J. H., & Way, B. M. (2007). Putting feelings into words: Affect labeling disrupts amygdala activity to affective stimuli. Psychological Science, 18(5), 421–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01916.x

Buhle, J. T., Silvers, J. A., Wager, T. D., Lopez, R., Onyemekwu, C., Kober, H., Weber, J., & Ochsner, K. N. (2014). Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: A meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cerebral Cortex, 24(11), 2981–2990. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bht154

Ochsner, K. N., & Gross, J. J. (2005). The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(5), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010

Keng, S.-L., Smoski, M. J., & Robins, C. J. (2011). Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: A review of empirical studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(6), 1041–1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006

Tang, Y.-Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916

Crum, A. J., Salovey, P., & Achor, S. (2013). Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 716–733. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031201

Skinner, E. A. (1996). A guide to constructs of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.3.549

👌🏽👌🏽👌🏽👌🏽